Looking Beyond the Headlines

Chaga’s Disease

Triatomine kissing bug (World Health Organization, Isaias Montilla).

Trypanosoma cruzi, the organism that causes Chagas disease.

Trypanosoma cruzi is the causative organism of Chagas disease that is vectored to humans by kissing bugs.

Chagas disease has long been branded as a problem in underdeveloped areas of the globe. It’s similar to how we think about malaria, yellow fever, and dengue fever - diseases that are “over there”. Recently, however, government and university health officials in California and the US want Chagas disease to be considered endemic to the US. Endemic means that the disease is here in the US, has been here and will remain here. Their PR campaign is therefore making headlines, and raising concerns, but for the wrong reason. People are focusing on the gruesome aspects of the disease and not about shifting resources to education and monitoring, which is the real point of the headlines.

Is Chagas Disease Endemic in the US?

Defining a plant, animal or disease as endemic can require discussion and debate among researchers and regulatory bodies. Endemic is defined as: restricted to or native to a particular region.

For Chagas disease, we know that it has been in the US, and all over the Americas, since prehistoric times! Can’t get more endemic than that.

Shifting Patterns in “Tropical” Diseases

The movement of tropical diseases toward higher latitudes warrants resources focused on education, prevention and monitoring. But we first need to come to grips with history.

History books are filled with facts about diseases long considered to exist in tropical regions despite the fact that malaria and Yellow Fever were rampant in northern Europe by the 1400s and all over the first American colonies in the 1600s. At the age of 17, George Washington first contracted Malaria and suffered with it the rest of his life and Alexander Hamilton contracted Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793, but survived.

The reason we consider these diseases as tropical these days is because we used pesticides in the mid-1900s to push back on the insect vectors, thereby pushing them out of our everyday lives. The US used DDT in the 1940s and 50s, and drained wetlands to reduce mosquito populations. Most US counties still have Mosquito Abatement Districts to monitor mosquito populations and their efforts ramped up following the entry of West Nile Virus in to the eastern US in 1999. But the combination of resistance against insecticides by mosquitoes, resistance against therapeutic medicines by the malaria organism, and a warming climate, populations of diseases and vectors are once again moving northward. The Zika virus was another recent example of how easily and quickly these organisms can push their current boundaries. And to paraphrase Ian Malcolm, bugs find a way.

The global map shows the reported distribution and intensity of the disease as of 2025. The darker colors indicate higher counts. Red indicates areas currently classified as endemic. Blue indicates areas where the disease is thought to be introduced or non-endemic.

US Distribution of the Disease and the Insect Vector.

The presence of the kissing bug is key, because if there’s no bug, then the disease cannot be transmitted to humans. Turns out kissing bugs that can vector Chagas disease are widespread throughout the US.

There are an estimated 300,000 people in the US that have the disease and most don’t know it.

Up to 100,000 have it in California. And roughly 20% of cases in California are autochthonous, meaning that the disease was acquired where the person lives, not from traveling abroad.

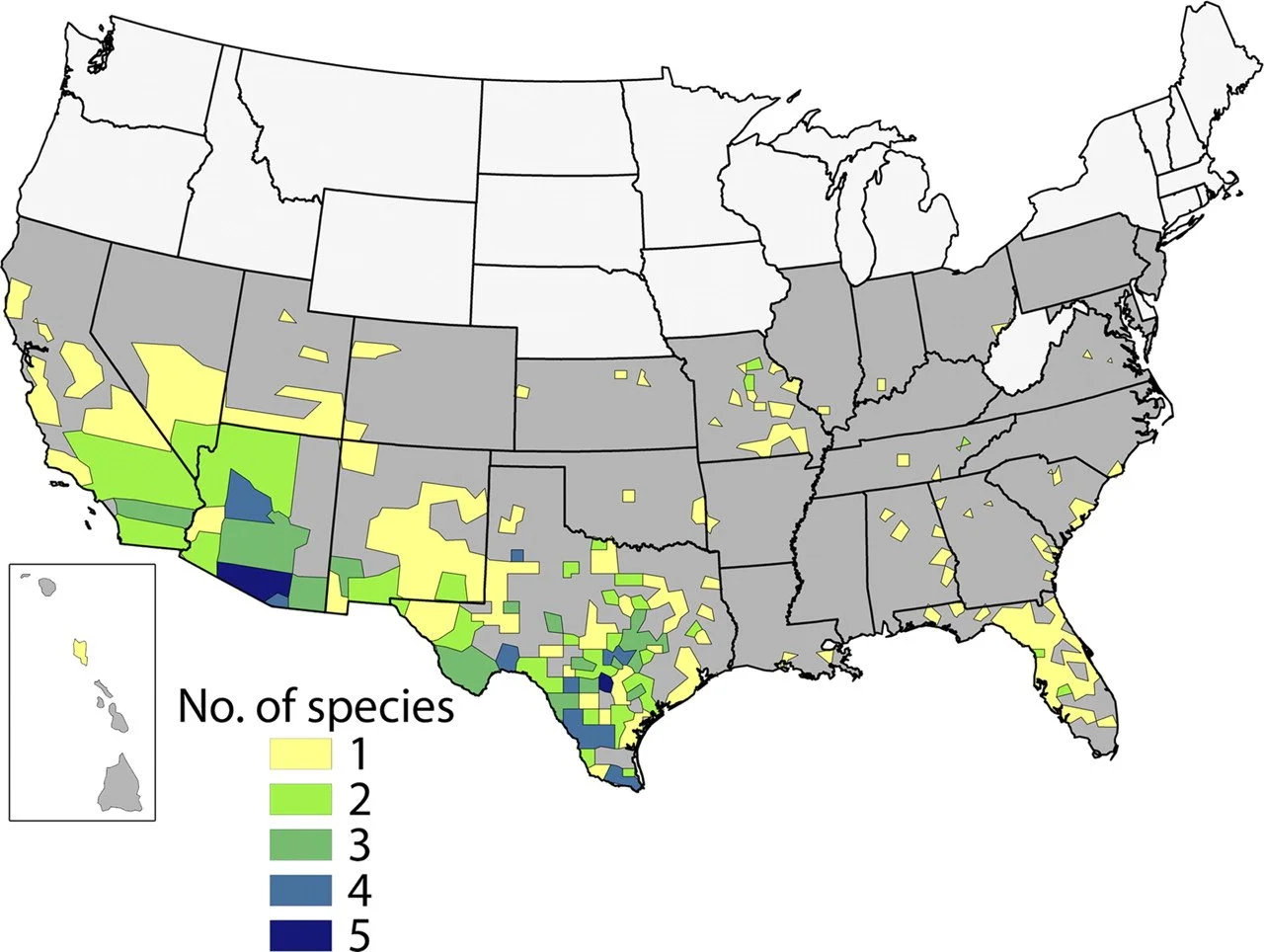

This US map is from a 2011 publication about the distribution of kissing bug species that can transmit Chagas in the US. There are now more states that have the kissing bug present, including Wyoming and Nebraska. The disease also occurs in most of the states with populations of kissing bugs. The warming climate has allowed the disease to expanded its range northward; a phenomenon that affects many other diseases and pests.

The Need for Reclassification

Considering these facts and its documented history, Chagas disease does appear to fit the definition of endemic.

If global and national health organizations reclassify Chagas disease as endemic to the US, the current distribution of the disease and its insect vector, will be more accurately reflected and open doors for resources and education.

Educating the public is key to successful disease management because it is curable when detected early.

How California Monitors Chagas Disease

At the time of this writing, doctors in Los Angeles and San Diego Counties are required to report instances of this disease. This means that if there is a case of Chagas disease in any other county in California, it will not be documented and added to any sort of database for analysis or referencing. Health officials want to change that. The hope is to raise awareness and change our approach to reporting. Reporting all instances of the disease will give us better data on the distribution of the disease and insect vector so we can put resources towards educating the public and support early disease detection in humans. Humans can survive this disease, but early detection is key.

Let’s Talk about Chagas Disease

A Blood-Borne Disease

Overview: If someone is bitten by a disease-carrying kissing bug, there’s a chance that the trypanosome parasite will enter the victim’s blood stream and begin an infection. There are two phases to the disease: acute and chronic. The initiation of the disease is the acute phase and is the only time you’ll have a chance at early detection and the hope of a cure. If after several months no action is taken, the disease moves into the chronic phase. At that point a person will have the disease until they succumb to a variety of ailments related to the parasites living and reproducing in their internal organs.

Disease Cycle - *trigger warning* extreme heebie geebies

The kissing bug insect is a blood-feeder and has needle-like mouthparts (=stylets) similar to a mosquito’s. Kissing bugs get active at night seeking out any animal with blood (including humans) to feed on. If it is a human, sleeping comfortably in their bed, a bug lightly crawls onto the unsuspecting victim’s head and moves toward areas with moisture (eyes, nose and mouth). They insert their stylets to tap into a blood vessel. As they do, they inject saliva that has both anesthetic and anti-coagulant properties so the victim doesn’t feel a thing and the blood flows freely. A bug will spend anywhere from 10 to 30 minutes engorging on blood. A crucial bit of information to mention here is that the kissing bug also will defecate fecal droplets on the person’s skin while it’s feeding.

Infection Process

If a kissing bug feeds on a human that is not previously infected with the Chagas trypanosome, when the bug next feeds on a different human, there is no threat of disease transmission. But, if the bug feeds on someone who has the trypanosome parasites coursing through their veins, then the kissing bug will ingest these parasites along with their blood meal. The trypanosome parasites will pass through the bug’s digestive system unharmed and are later expelled in the bug’s feces.

The Insidious Part

There is no trypanosome parasite transmission to the human victim while the bug is feeding. But remember, they defecate near the feeding site as seen in the photo (yellow arrow). It’s not bad enough that they just took a bunch of your blood, but they poop on you to boot! That’s like the old saying, “rubbing salt in the wound.” Which is an ironic choice of adage because that’s what it takes to get the disease going. After the kissing bug feeds and moves on, the wound gets itchy just like a mosquito bite. The sleeping individual rouses enough to start scratching at the area. The feeding site is littered with droplets of kissing bug poop and in that poop are thousands of parasites anxiously waiting to get rubbed or scratched into the wound. If they don’t, they die on the surface of the skin. But if they do, then the trypanosomes access a blood vessel and enter their new host’s blood stream and that starts the infection. It is remarkable to think that the victim self-infects by mindlessly scratching the parasite-laden bug poop into the itchy bite wound! On top of that, this newly infected person is now a reservoir for the disease-causing trypanosome parasites which can lead to more and more human infections.

A kissing bug defecating fecal droplets (arrow) teaming with 1,000s of trypanosome parasites. Those parasites must get rubbed into the feeding wound created by the kissing bug’s stylets to start an infection in the person being fed on; otherwise, no infection.

Early Sign of Chagas Disease - Romaña’s Sign

The early warning sign of Chagas disease is swelling near the bite area, typically the eye lids, nostrils and lips - hence the name kissing bug.

Swelling after the infection has begun can happen, but not always. Swelling or not, this is the acute phase of the disease and is the one sign that should prompt a visit to a doctor for appropriate medical treatment.

The Chronic Stage and Ultimate Demise

If left untreated, most people enter an asymptomatic chronic stage of the disease. The trypanosomes move through the blood stream and settle in various internal organs. Over time, the organs, in response to the infection, begin to swell. After years, or even decades, the enlargement of the heart and/or colon leads to life-threatening complications.