The Evolution of Conflict Avoidance

When I was a graduate student, from 1987 to 1992 - I studied a group of flies - fruit flies – in the family Tephritidae. It is a large family of about 4500 species worldwide and includes globally significant pests like medfly, Caribbean fruit fly, Oriental fruit fly, and melon fly. But in California, we have about 150 species and the larvae feed on plants in the family Asteraceae, such as California aster, Coreopsis, goldenrod, canyon sunflower, sagebrush, and thistles. Larval feeding is often on a particular plant part, like the seeds or receptacle; some bore into the crowns of herbaceous annuals or biennials; others form galls.

My studies took place in remote backcountry wilderness sites from Otay Mesa to the Chiriaco wilderness; Onyx Peak to Hidden Springs, and many places in between. I spent a lot of hours throughout the seasons observing these flies in action. These flies also are slow moving and don’t get started with their daily activities until around 9 am. I was lucky my study subjects liked to sleep in.

Much of my research is summed up in two publications. See Resources below.

A typical setting for studying tephritids in California.

Tephritid flies are quite colorful. Two of my favorites are Paracantha gentilis (Photo credit: icosahedron @inaturalist), left, and Eutreta diana (Photo credit: Brandon Woo).

Avoidance of Conflict

One of the main things I learned from this work is that a significant outcome of the evolutionary process is the avoidance of conflict over resources within the same trophic level. Resource partitioning is what allows for several different species to coexist on a single type of resource, thereby creating a diverse and resilient living system. This discovery is what has flavored my world view and my approach to pest management solutions in agricultural systems throughout my career.

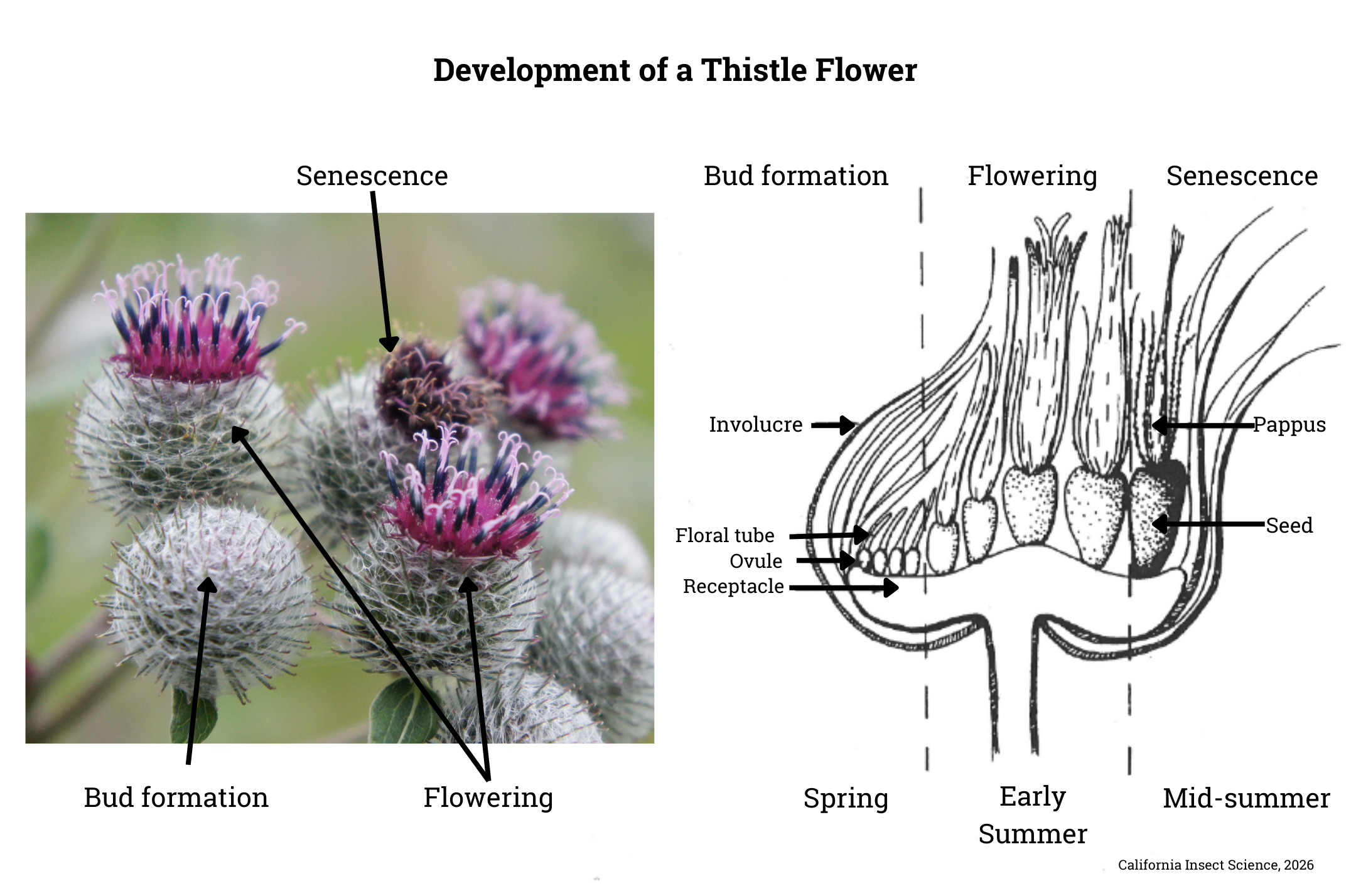

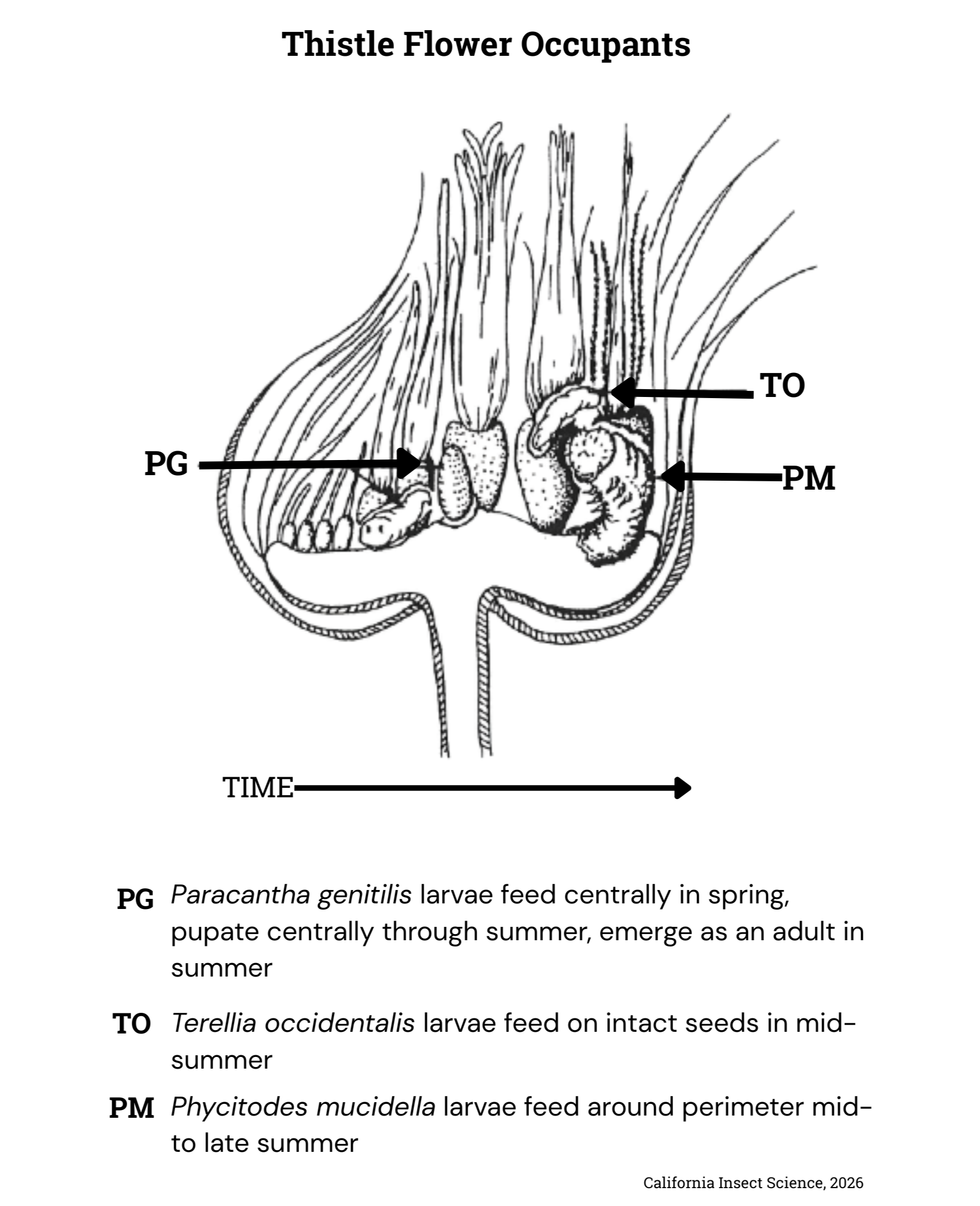

Therefore, the crucible of life’s diversity on Earth can be as commonplace as a daisy flower. But let’s not assume that a daisy flower is ordinary or simple. My most detailed studies involved thistles. Structurally, they are quite complex and offer up a variety of resource types, especially as the flower ages from a bud to a mature bloom. There are involucre (bracts), a receptacle, ovules, floral tubes, achenes, and pappus, each of which offers up a nutritious source of food. The various insect species that inhabit and make a living feeding on thistles evolved to become specialized feeders on these different types of resources. Like Paracantha gentilis, whose larvae feed centrally in the flower head on the developing ovules and then create shallow feeding wounds in the receptacle’s surface to slurp up the pooling plant sap. Each species in the group adapted unique ways to feed. That allowed for multiple species to occupy a single flower head contemporaneously and have plenty of food for all to complete their development through to adulthood. It also allowed for plenty of thistle seeds to remain uneaten and the thistle population to set seed and keep reproducing.

The photo shows a cluster of thistle flower heads in three stages of development. The diagram on the right documents what is happening inside the flower heads during the three stages from bud formation to senescence.

The same diagram but superimposed with the insect species and where they feed in the head through time. Paracantha gentilis typically occupies the flower head by itself in the spring as the bud is developing into a blooming flower.

An Insect’s Feeding Niche

Insect feeding strategies are hardwired. So even if just one species were to occupy a thistle flower, the larvae stay in their lane, so to speak. They don’t capitalize on the lack of other occupants to start feeding on other parts of the flower. They just do what they have evolved to do - complete their development and move on.

What an insect feeds on and the particular way it feeds is referred to ecologically as a niche. The more complex the resource, the more potential niches (=plant part) available for insects to exploit, adapt to, and become a specialized feeder. In this manner, the mechanisms of evolution allow for species to find ways to gain enough of the resources they need to complete their development without having to battle it out with other species over the same resource. Such conflict leads to a lot of unnecessary strife and mortality. The main driver in biology is for an individual to live to a reproductive age so they can pass their genes along to the next generation. Philosophically, it would be nice to not have to fight others for every scrap of food you need in order to make that happen. And that is what I see as one of evolution’s best outcomes.

Basic Research Informs Real Pest Management Solutions

What impact does the evolution of specialized feeding roles have in an applied setting? All of the insect pests we encounter in our cropping systems evolved somewhere on a plant in the presence of other insect species. They have adapted feeding strategies that serve them well in that native context.

Insects now exist in our managed cropping systems without the other members of their native insect community, but they continue to maintain their evolved feeding strategy. We see them feeding on seeds, or foliage, or boring in a stem, or mining a leaf. And they stay in their lane. They do not co-opt additional free resources which would create even more feeding damage to our crops.

Specialized feeding methods (clockwise from upper left): skeletonizing, phloem feeding with piercing-sucking mouthparts, leaf mining with modified mandibles, and foliage feeding with chewing mouthparts.

Understanding the pest species feeding role is vital to the development of an effective management plan. It helps us determine which are key pests - is the feeding direct on the harvested commodity or indirect on some other part? For example, in citrus we know that California red scale is a key pest because it damages the fruit, but a mature citrus tree can withstand some feeding pressure from brown soft scale.

California red scale heavily infesting fruit (photo, Joel Leonard) and Argentine ants farming brown soft scale on twigs.

Each insect pest has its evolved feeding role and entomologists have documented them. We know what they feed on and how their mouthparts enable such feeding. We know if they feed quickly or slowly; if it’s confined or exposed. We know these fundmental but important factors because someone, somewhere, did the basic research. And all of these factors inform what types of methods we can use to reduce pest numbers and when it’s best to use them.

Resources

Headrick, D. H. & R. D. Goeden. 1995. Reproductive behavior of California fruit flies and the Classification and Evolution of Tephritidae (Diptera) mating systems. Studia Dipterologia. 1: 194-252 and Headrick, D. H. & R. D. Goeden. 1998. Biology of non-frugivorous tephritid fruit flies. Annual Review of Entomology. 43: 217-41

Headrick, D. H. & R. D. Goeden. 1998. Biology of non-frugivorous tephritid fruit flies. Annual Review of Entomology. 43: 217-41