Mutualism

Mutualism is one form of symbiosis that occurs when both species involved benefit from the interaction.

The Definition of Mutualism

Symbiosis is a familiar term to most, but it describes a host of lesser known complex interactions.

There are three main categories of symbiosis: parasitism, commensalism, and mutualism. The categories are based on outcomes for the members involved in the interactions.

Parasitism - one species benefits while the other species is harmed.

Commensalism - one species benefits and the other is neither harmed nor helped.

Mutualism - both species benefit from the interaction. It's a win-win for the members involved, but not for those of us trying to grow plants.

The photos below represent one example of mutualistism. In this scenario, there are three players: a holly plant, Chinese wax scale and Argentine ants.

An Example of Mutualism

All three players above have been introduced, either accidentally or on purpose, to California. Common holly originally evolved in Europe, the scales, contrary to their name, originated in South America, as did the ants. While they evolved elsewhere, there are conditions here in California that have allowed for their establishment and survival; basically, wherever there is irrigation water. There’s also something subtlety remarkable happening with their interactions. They carry on with long-evolved ecological roles and behaviors here, just as they did back home, but with species that are evolutionary strangers. And so the plant grows, the scales feed on the plant’s sap (aka phloem), and the ants harvest and feed on the scale’s honeydew - exactly as their distant cousins still do back in their homelands.

Holly plants often look quite healthy from a distance. But upon closer inspection, you may see Chinese wax scale insects encrusting the lower branches and leaves. Scale insects do not look like a typical insect. The adults have no visible legs, no wings, no eyes, no antennae. They do, however, have the ability to feed and reproduce, which are two of the most important features for an insect. The tools for feeding are housed beneath the protective waxy, white covering. Their feeding ultimately leads to excretion of the honeydew that ants love so much.

From Phloem to Honeydew

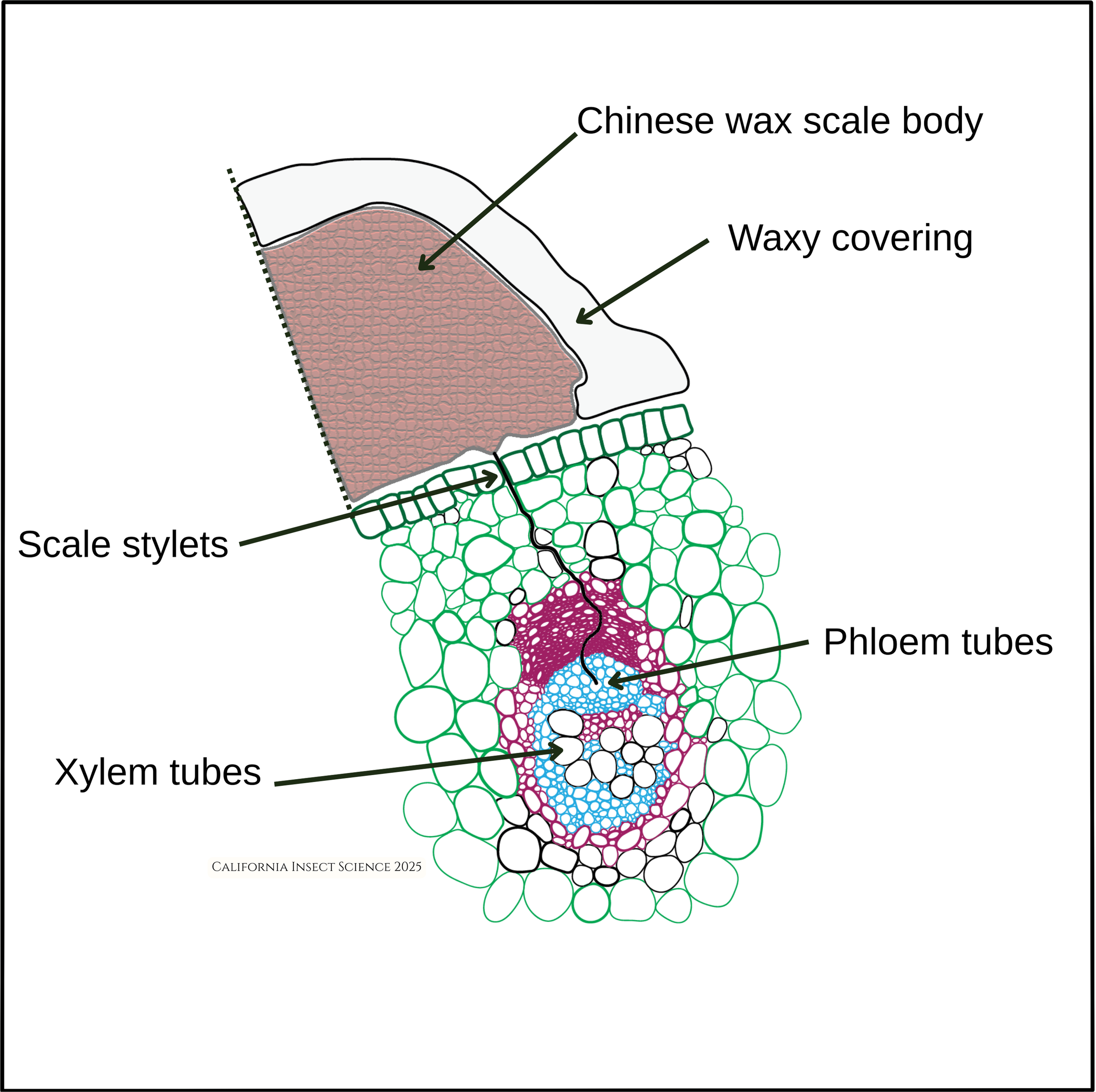

The scale’s feeding process is key to the concept of mutualism in this scenario. Scales are hemipterans in the suborder Sternorrhyncha. A key character of this group is their mouthparts: four stylets, grouped to form a needle-like probe, that is used to pierce plant tissue and draw out the phloem. This feeding process is analogous to how mosquitos feed on a vertebrate's blood. However, unlike a mosquito, the mouthparts of Chinese wax scale are inserted into the plant where it settles, never to move again. They spend their entire adult life stuck in one spot on a plant feeding on phloem 24/7/365. That would be like us using a straw on an endless supply of milkshake all day, every day. And as long as the plant is healthy, it provides a continuous stream of phloem for the scales.

When the stylets are inserted into the plant, they maneuver in between the cells seeking out the place with the phloem tubes. Once there, the tip then pierces one such tube and the process of drawing out the phloem begins.

Phloem is a good resource full of sugars, amino acids, and a whole host of other nutrients, but it is not nutrient dense. Therefore, these tiny insects must consume a lot of it. Their digestive system filters what they need and shunts the remainder out of the body as a sugary excrement called "honeydew." Lovely. Below is a video showing a scale insect feeding on a holly stem and flicking a droplet of honeydew away from the colony. Honeydew is sticky stuff and the scales try to keep their feeding area somewhat clean.

The video captures the moment when a Chinese wax scale flings a droplet of honeydew.

Honeydew production is non-stop and it can accumulate on the plant's surfaces leaving a sticky mess, which draws in the third member of this mutualistic interaction, sugar-loving Argentine ants. It is not uncommon to have thousands of these ants around the landscape searching for food. When they locate the honeydew splatters on the plant surfaces, they continue searching to find the source. When they discover a colony like the Chinese wax scale, they then begin harvesting the honeydew. They prefer to take it directly from the scales and the scales readily oblige, often waiting for a tap of the ant’s antennae to indicate the ants are ready to receive the food. Kinda like a honeydew drive thru. The ants ingest the honeydew and store it in their crop - a food storage sack in their digestive system - and return to the nest where they regurgitate the honeydew for nest mates and developing ant larvae to feed on. I never said bug biology was pretty.

The Mutual Benefit of Mutualism

In this scenario of interactions, plants make their own food - phloem. Scales consume the phloem to reproduce and make more scales, and excrete the excess as honeydew. The ants eat the scale’s honeydew for their own nourishment and for their nest’s reproduction. So, which interaction is mutualistic? The plant can handle a scale infestation even though it’s losing a lot of phloem. Therefore, the interaction between the scale and plant is commensalism. There is no real interaction between the ant and the plant except that it serves as a host for honeydew producing scales, which would be commensalism as well.

For this to be mutualism, the scales also need some sort of benefit, such as protection from predators. It turns out, these honeydew producing insects need protection to survive. Adults scales can’t move, thus they are defenseless and often find themselves as the main menu item for dozens of parasitic and predatory insects including ladybird beetles, green lacewings, and syrphid flies. However, the ants are highly protective of their honeydew-producing insect colonies and will fend off or kill any predator that comes near their honeydew source. Therefore, protection from predators is the benefit for the honeydew producer in this mutualism equation. The ants are, in essence, treating these scale colonies like a herd of livestock. And in return, the ants get the food they need, resulting in a mutually beneficial arrangement.

The photo here shows a female scale turned over, exposing the cavity beneath the waxy layer filled with dozens of eggs. Each female produces at least this many offspring and that is why their populations explode so quickly.

The Impact of Mutualism on Plants

The ant / honeydew mutualism interaction is a constant challenge for people growing plants for work or pleasure. We know that honeydew producing insects are significant pests on nearly everything we grow, simply due to their feeding and the resulting mess from honeydew. But if Argentine ants are present, they exacerbate the problem by preventing predators and parasitoids from doing their job of preying upon these pests. And the resulting damage to plants isn’t trivial.

Significant loss of phloem can cause wilting, poor plant growth, reduced yields and susceptibility to other problems, similar to having a compromised immune system. If the loss of phloem is unabated, it can lead to plant death, as seen in the photo on the left.

Disease vectoring. In another complicated twist of biological interactions, certain plant diseases take advantage of the way honeydew-producing insects feed. A virus or bacteria can hitch a ride on or in the stylets and get inserted into new host plants, thus perpetuating the disease cycle. Think dirty needle syndrome.

And sooty mold. The ants can’t eat all the honeydew produced by these colonies and a lot of it ends up accumulating on leaf surfaces where it forms a sticky layer. Honeydew provides the perfect place for naturally occurring fungal spores on leaf surfaces to grow and develop into a dark, crusty mat called sooty mold (center and right photos). The mold is unsightly, but the real problem is that it blocks sunlight from reaching the leaf cells, thereby reducing photosynthesis.

Now with a better understanding of mutualism between ants and honeydew producing insects, it begs the question: how do we minimize the damage to plants? Start by managing the ants.

For information and tips on managing ants in the home and landscape, visit our blog on Argentine ants and the page on Argentine Ant Management.