Aphids

A review of aphid feeding, reproduction, growth and molting, and dispersal

Aphid Feeding

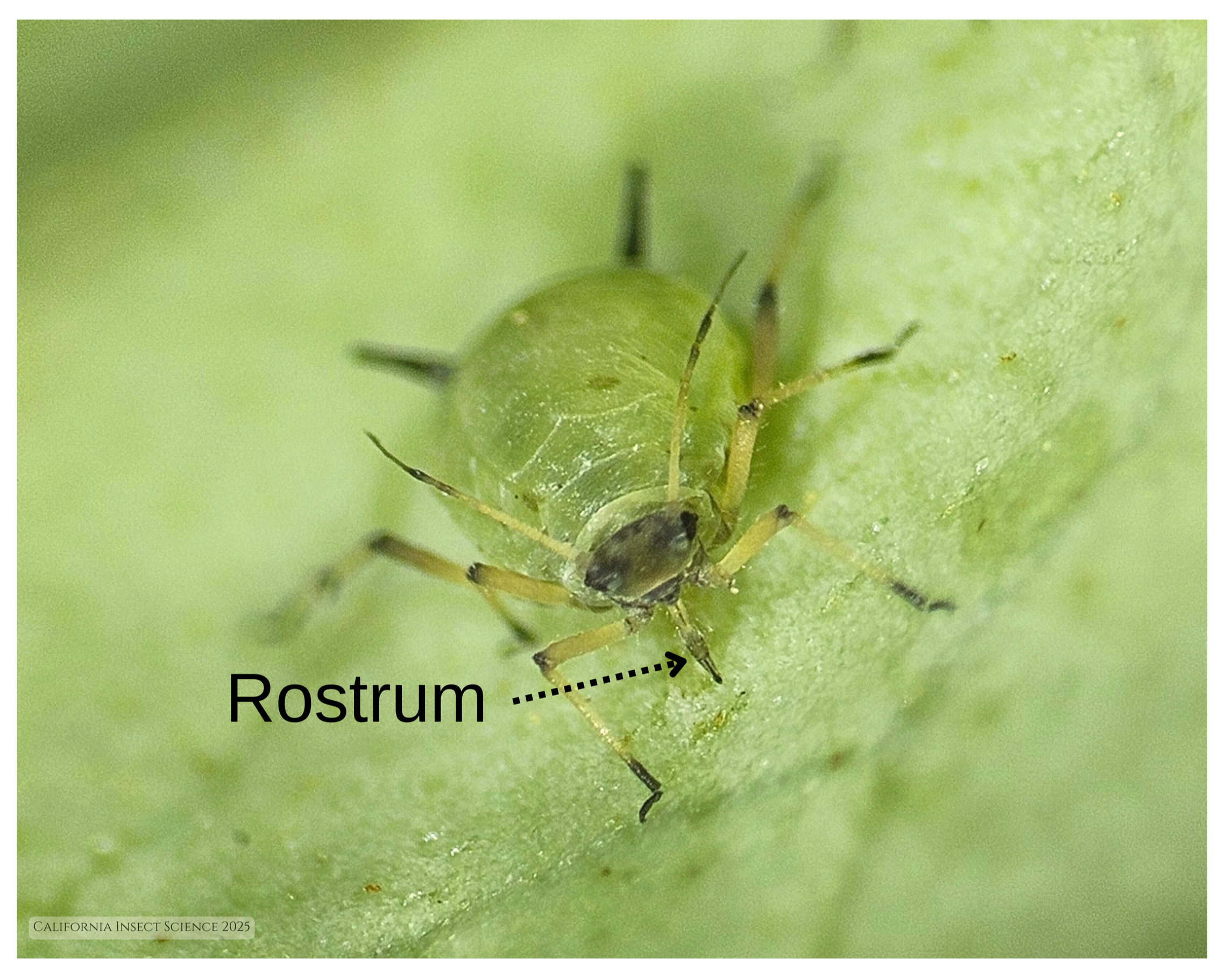

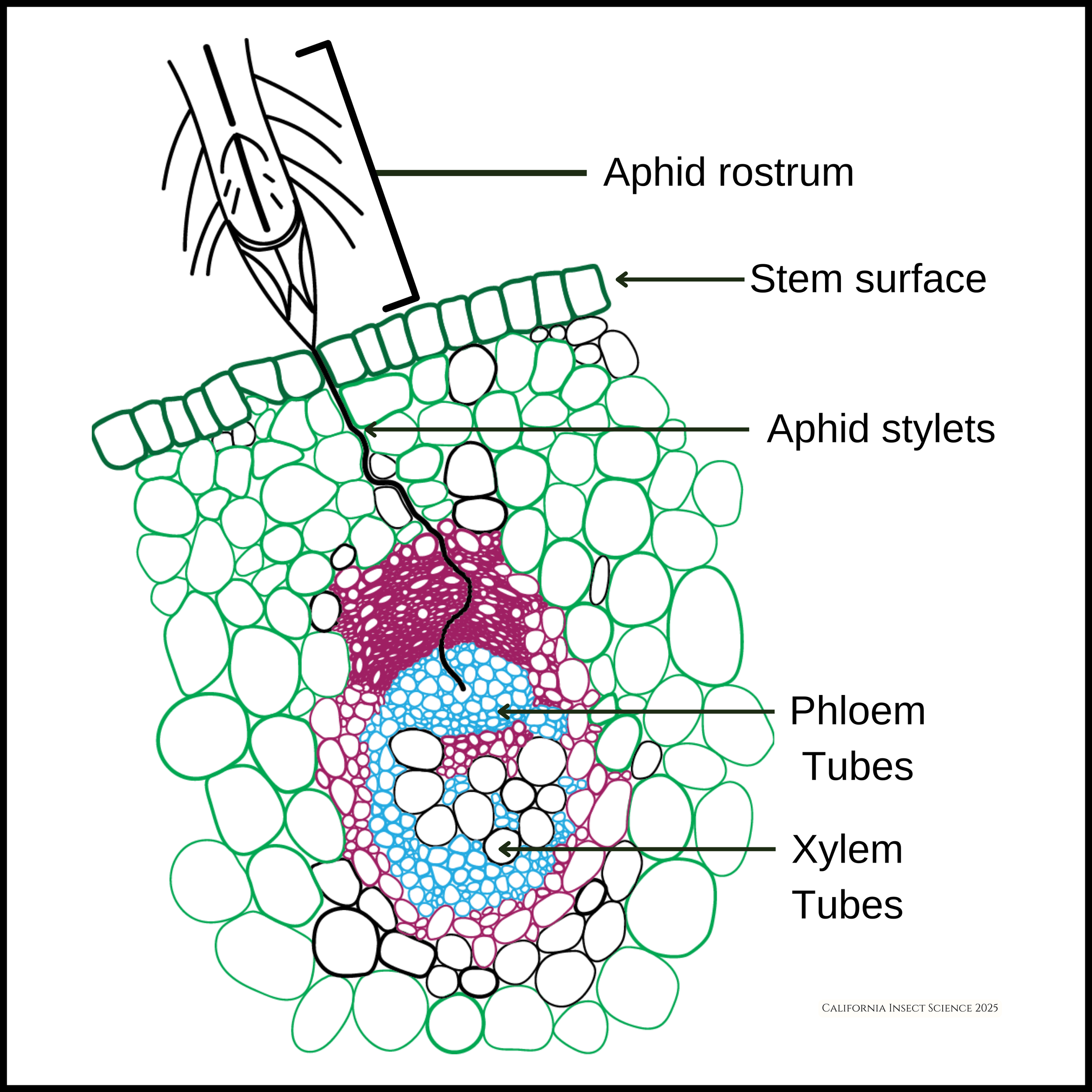

Aphids feed on plant sap, more accurately called phloem, by using their piercing/sucking mouthparts, comprised of a rostrum that holds needle-like stylets. The stylets pierce the plant and snake their way in between cells to reach the vascular tubes that carry the phloem. In doing so, aphids inject a lubricating saliva to help glide the stylets around the plant cells without disrupting them. Most aphids feed on newly developing or otherwise tender plant tissues. Older tougher tissues are too difficult to penetrate and the phloem tubes may be out of reach of the stylets. The photo shows the aphid and its rostrum which remains external to the plant while feeding. Th diagram shows a microscopic cross section of a rostrum as the aphid feeds on a stem and the stylets wind their way in between the cells to get to the phloem tubes.

Phloem is typically under pressure, and when the stylets pierce a phloem tube, the fluid is easy to uptake. Not at all like us trying to drink through a straw. The phloem is in abundance, but is nutritionally unbalanced. It contains a lot of carbohydrates, but limited amounts of lipids, amino acids and other micro-nutrients. To get all the food they need for growth, aphids must take in a lot of phloem. They filter out what’s needed for nutrition and eliminate the rest. The rest is an excreta that is a clear, very sugary fluid called honeydew. They expel their honeydew waste one droplet at a time, every 5 minutes or so. When they produce a honeydew droplet, aphids lift their abdomen upward, hold the droplet up above the body and away from any other nearby aphids. The droplet for some aphids is encapsulated in a thin, waxy coating that is then dropped. Depending on the position of the aphid on the plant, the coated droplet may roll off the plant onto the ground or away to some other part of the plant. Other aphid species will fling an uncoated droplet away from their body which also may fall to the ground or splatter onto another part of the plant. Preventing an accumulation of honeydew near their colony is important because the sticky honeydew can become a significant problem for the aphids. Aphids can get stuck in it or even suffocate if there is too much build up. Aphids rarely stop feeding. They feed while birthing and when being attacked by predators. Therefore, managing honeydew accumulation is a significant daily concern for aphids and why they have evolved several ways to deal with it.

A droplet of honey dew developing on the upraised abdomen of an aphid mother. The aphid mother is surrounded by the daughters she birthed earlier in the day.

A close up of a honeydew droplet that will go through the process of developing a waxy coating.

Two droplets of honeydew with waxy coatings that keeps them safely contained.

Toxic Saliva

The saliva of some aphid species is toxic to the plants they feed on. As more and more aphids feed on a newly developing leaf, the toxic saliva builds up and deforms the expanding leaf tissues. The yellow arrows in the photo point to curled citrus leaves. The next photo is a curled peach leaf caused by the saliva from a large colony of aphids. The distorted leaf creates a protected habitat which is important for the aphid’s survival and growth. The damage to the peach leaf is unsightly, but the leaf still has the capacity to photosynthesize.

Aphid Reproduction

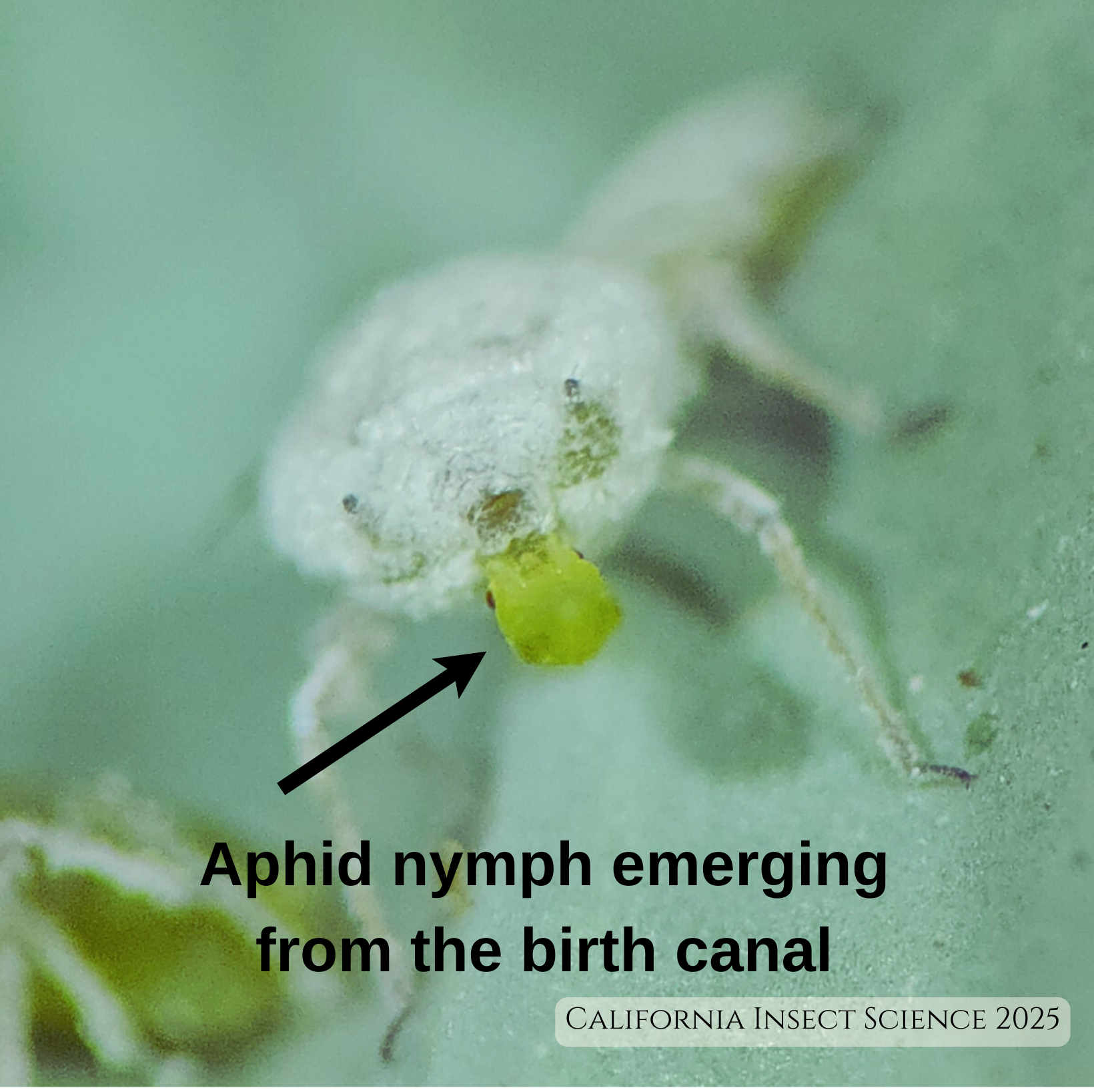

Aphids are adept practitioners of reproduction. It is their superpower. They have complicated life cycles and make use of two different reproductive strategies to ensure a continual output of female offspring; one of which skips the need for mating altogether. The photos show wingless adult females giving birth to female nymphs, which they can do several times per day. Because of this, aphid populations can undergo exponential growth in a short period of time. It goes something like this: if a single female can give birth to 5 daughters per day, then by the end of the week one female has 35 daughters. It takes about one week for a newly born aphid nymph to reach adulthood and begin birthing her own daughters. Therefore, by the end of a 30 day month, one female aphid can give rise to a population of 18,476,215 aphids. They are reproductive machines and this is why they are so difficult to control once they get started. Even with all the predators and parasitoids that attack them, their reproductive output can outpace most mortality factors, except for one - hot weather. Many aphid species cannot withstand sustained temperatures of 90°F.

Aphid mothers are efficient. They continue to feed during the birthing process and often birth to 2-4 daughters in quick succession over the course of an hour or so. They then take a break for a few hours. The constant intake of phloem aides her embryo development for the next batch of births.

Nymphs emerge from the birth canal abdomen-first (like a breech birth in humans). They are encased in a thin membrane that quickly falls away. Once their legs are free to move, they grab onto the leaf surface and typically move under the mother for a brief time, insert their stylets into the plant and begin feeding and growing immediately.

Aphid Growth and Molting

Aphid nymphs grow rapidly. Most species molt four times before they become an adult, and molting is the only way they can accommodate the rapid increase in size. The molting process for insects is a complicated process that will be discussed in a separate section in General Entomology. At its simplest, an insect, such as an aphid nymph, develops a new cuticle inside its old one and then bursts out of the old one and sheds it in a process called ecdysis. The photos illustrate a sequence of steps in the molting process. The white structure is the old cuticle sloughing off the new, larger nymph. The old cuticles are sticky and they remain stuck on the leaf surface after the aphid walks away. In fact, even long after the aphid population has died out, you’ll still see all of the cuticles remaining as a tell tale sign that an aphid infestation had been there.

Aphid Dispersal

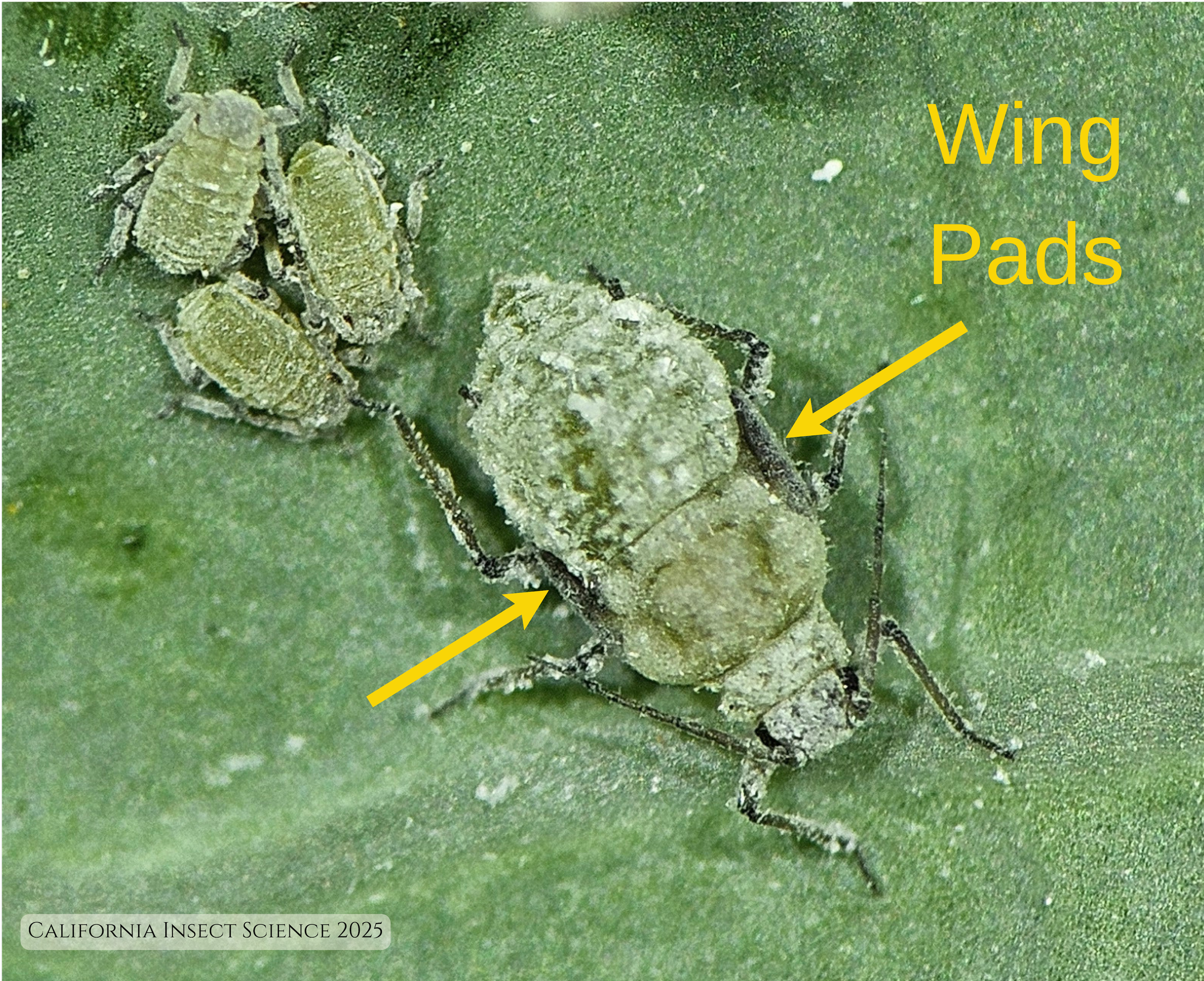

Organismal dispersal occurs in response to environmental stressors or seasonal cues. In a given population, some aphids will develop wings and fly off to find new resources in response to a decline in resource quality or changes in the environment such as day length, temperature, etc. Dispersing aphids begin to show anatomical differences in their late nymphal stage, such as a constricted waist and external wing pads that will become fully formed wings when molting to the final adult stage. These winged females will give birth to wingless females once they arrive at a suitable host plant. Then, the development of a new colony will begin.