Justifying Biological Control…Again

Me: (30 yrs old wearing a UCR entomology t-shirt, shorts and top siders with white socks, knocking on a door in a neighborhood in an area being negatively impacted by an invasive insect pest): “I’d like to release a small number of stingless microscopic wasps into your yard”

Me, again: “No, the wasps won’t harm anything else”

And again: “We’re releasing them to control insect pests, so you don’t have to spray pesticides”

And again: “Without their insect hosts the wasps just die; they don’t attack anything else”

The responses following these real-life conversations I’ve had with bewildered homeowners were one of three: enthusiastically agree to allow releases in their yard, apathetically agree to allow releases in their yard, or an abruptly closed door.

At least some of the homeowner responses allowed us to move forward with trying to get the parasitic wasps established and working in the environment. You can read about an example of a receptive homeowner scenario that had a surprising, unrelated twist.

But how do biological control practitioners even get to the point of asking homeowners for permission to release parasitic Hymenoptera in their yards? It’s a wild ride to be sure. And we once again find ourselves justifying the use of biological control to the public for the control a recently invasive, devastating species of insect; something we’ve been doing in California since 1889.

For me, after 30 years, it can be frustrating to have to keep justifying biological control. My hope is that you’ll gain some insights here that will help you be an ambassador for biological control in your circles, whether you’re an ag. professional or a home gardener or both, especially now that biological control is being embraced by many groups that once were skeptical.

Example: Spotted Lanternfly

What prompted this blog was a New York Times opinion piece by Andrew Zaleski (July 2, 2025) about the use of biological control against the spotted lanternfly. The title: A Plague of Pests Is Coming for California. Here’s How to Stop It. Sounds scary.

Spotted lanternfly life cycle ©Oxford University Press.

Spotted lanternfly was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014 and has now spread to 15 states and is wreaking havoc on the east coast. The concern is that it will make its way westward and eventually arrive here in California.

Spotted lanternfly, like many other invasive species, attacks plants that are important agriculturally, but also occur in urban landscapes. That means invasive spotted lanternfly populations will establish across distinct, autonomous boundaries – agricultural lands, government-owned lands, First Nations lands, and your yard. The folks who have governance or control over what happens across these diverse lands often have widely different points of view regarding their care.

When an invasive species attacks a plant that is mainly grown for agriculture, decisions about the care and protection of that plant generally do not need to involve the public. Agencies such as the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA), the Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR), CalFire, and local agricultural commissioner’s offices make decisions to ensure public health and safety.

But when invasive insect populations blow up in all areas - agriculture, urban, and natural areas - then many more interest groups get involved and want to have a say in how scientists and regulatory agencies will respond.

The New York Times article was a voice from the public sector using a global platform to examine concerns about using biological control for spotted lanternfly. The article ended up being good, but to get people to read it, the editor opted for a clickbait approach with the title and the introduction laced with scary wording, some foreboding, and a dash of impending doom. In my opinion, that’s not a good way to start a discussion about biological control, a pest management tactic that can be a concern with those outside of agriculture, as demonstrated with my little door-to-door scenario above.

We are going to need biological control for spotted lanternfly, a species that will cross all of the borders mentioned above. That means we need to have as many people as we can knowledgeable about the use of biological control. It means educating the public.

I discovered early in my career of implementing biological control releases, that if I was releasing a predatory beetle, all I had to say to a homeowner was “I’m releasing ladybeetles to eat your pests” and there was no issue.

A convergent ladybird beetle, an icon of “feel-good” pest control.

But if the biological control agent was a parasitic wasp and I said to a homeowner “I’m releasing wasps into your yard to eat pests” all kinds of alarm bells went off in people’s minds. I learned to describe parasitoids as stingless, microscopic wasps. That was a more palatable description that at least delayed a reflexively negative response. But the word wasp was the issue.

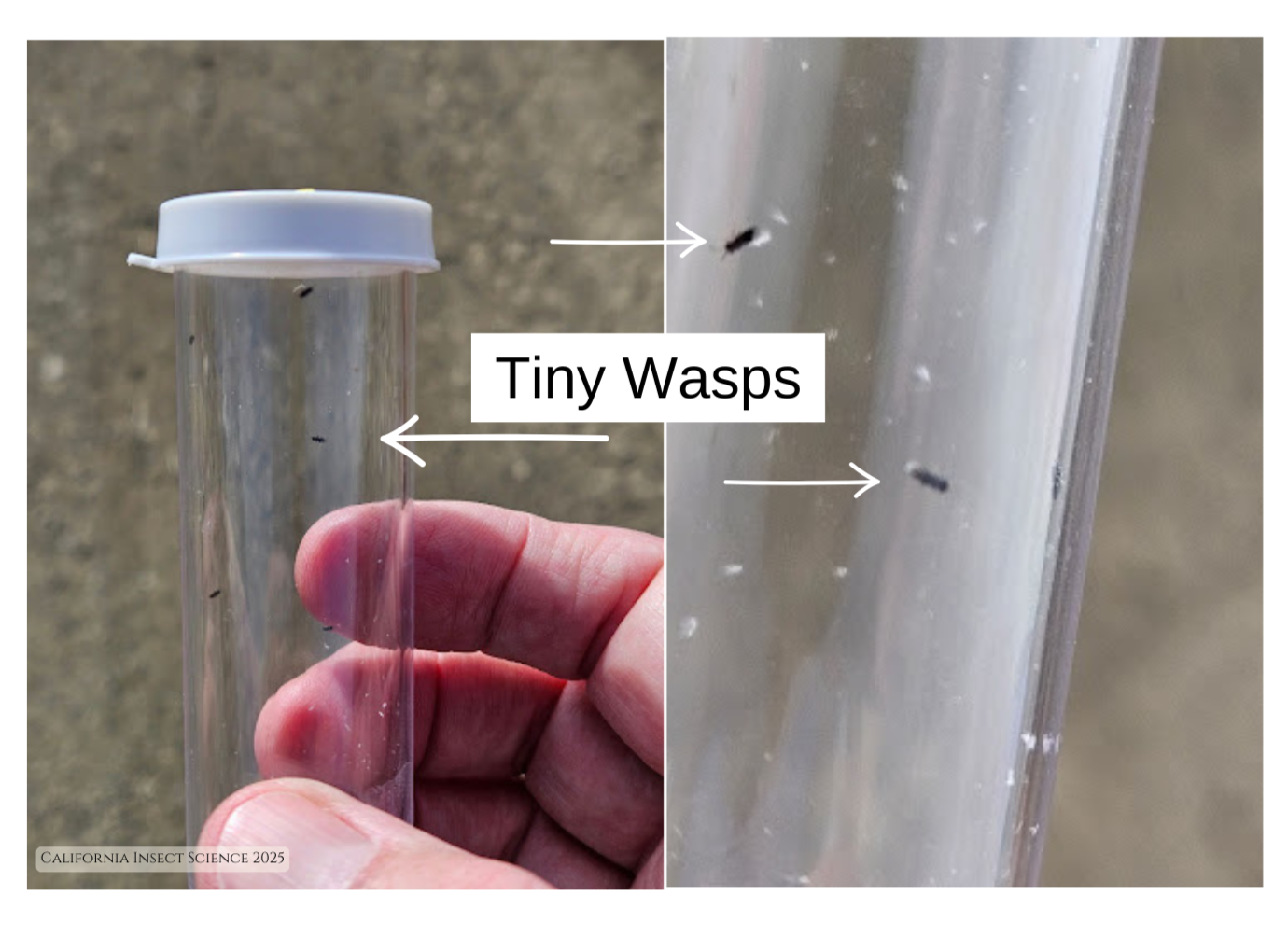

So we have a PR problem in biological control. Ladybeetles are seen as good, and wasps are seen as bad - but wasps are the main agents used for most biological control programs. The following photo shows a recent example.

Photos can be a first step toward understanding so I’m showing you a current example of releases of stingless microscopic wasps from plastic tubes in an olive orchard for the biological control of a new invasive pest in California, the olive psyllid. The wasps have been certified safe and the release program is going remarkably well. Hopefully, they don’t look menacing to you.

And stingless wasps will be the main agents used in the biological control program against spotted lanternfly.

That’s why I get annoyed with articles like the one in the New York Times. Starting off by inflaming public fears, then spending the rest of the article trying to convince them it’s all okay doesn’t seem to be a good strategy, especially in our current science-wary society.

The Times article also delved into some perceived fears regarding the release of biological control agents. It rehashed debunked, dire predictions from decades ago as part of the author’s journey of discovery before eventually finishing with his realization that biological control is “…more nuanced, and even more effective, than I thought, and society’s view of how to combat invasive species ought to be more generous to solutions that, at least on the surface, seem radical.”

Biological control isn’t radical, it’s common sense, with an excellent track record going on nearly 140 years. If there is an insect population that’s established in a new area and has nothing to keep it in check, then we need to restore ecological balance with biological control agents from the native home that are best adapted to finding and eating or parasitizing them. It's time to accept that biological control is a valuable and necessary tool for pest management and that the stingless microscopic wasps, just like the ladybeetles, are our friends and not to be feared.

Part of the rationale for our California Insect Science logo was to make a friendly-looking, unassuming, delicate insect with pretty green eyes, to help allay fear of wasps.

Frida the Wasp. Isn’t she lovely?

And it’s why I want to bring to your attention the work of Sloan Tomlinson, aka That Wasp Guy. He is an artist, photographer, researcher and educator sharing the beauty of what he refers to as the most-maligned insects, wasps, on his Instagram account (@thatwaspguy). His photography of micro-hymenoptera is outstanding and I look forward to his “Tiny Tuesdays” posts where he features the smallest of the small wasps. His excellent biological information along with incredible photos help bring these little beings to life. His cool t-shirts also are excellent outreach and educational tools.

There needs to be additional efforts to help shine a positive light on these little critters and showcasing all their benefits. Even just sharing validated information on personal social media accounts can help. The fact is, there are more parasitic Hymenoptera species in the world than there are plants, vertebrates, microorganisms, and other invertebrates combined! And without parasitic Hymenoptera, our ecosystems would simply collapse. They are key to keeping the fabric of life from unraveling. And if used wisely, they also can help keep our managed ecosystems, as well as natural ones, from doing the same.