We Gotta Talk About Pupation

There is a persistent myth regarding insect pupation. It goes like this: when an insect pupates its body completely liquifies into a soupy goop and then miraculously regenerates into an adult insect with tissues, organs, exoskeleton, wings, etc.

If you’re a cup half-full kind of person, you might forgive this myth by saying there’s a kernel of truth there. But, if you’re a cup half-empty kinda person, you’re going to say, uh no, couldn’t be further from the truth. I’m going to lean into the half empty view for this blog.

And I also want to lean into the poetic nature of the truth about insect metamorphosis. It is a timely topic as we head into the winter months. Typically a time of reflection, a time of quiescence, a time for cycles to end and the hope for new ones to begin. There are human rituals and stories aplenty recognizing the significance of life’s cycles spanning from the endless back and forth migration of Persephone to Mufasa’s Circle of Life soliloquy belted out in song by Sir Elton.

Many holometabolous insects are entering their pupal stage here in the fall, using this period to wait out the months where the environment is too cold and/or lacking in food. Then when the season changes, as the warmth arrives along with abundant food, they are ready to awaken, continue with their life and bring forth the next generation.

But what the heck? No, they don’t turn into a bucket of soup during this process. So, let’s get some things straight and find the real poetry in the process.

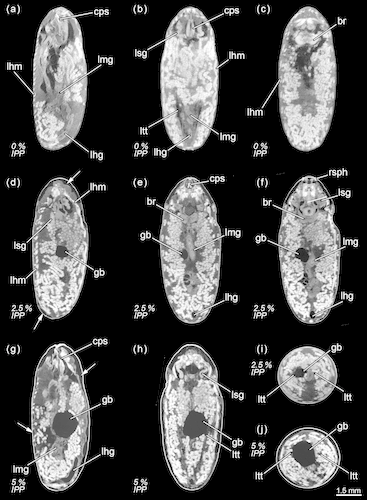

Moth pupa labeled to show the developing insect parts within.

See for Yourself

If you happen to be digging in the soil, perhaps in your garden, and you come across a small brownish pupa like the one in the image, take a moment and do something for me. Give it a gentle squeeze, or a tiny, little poke. Then watch it squirm. If you have a few minutes more to spare, set it in the soil, sit back and watch as it starts to rotate its abdomen and eventually “screw” itself back underground to a protected location safe from predation by birds and the like.

So, tell me, how does a bag of liquified soup do that? The answer is easy, it is not a bag of liquified soup. It has muscles. How does it know it isn’t under the soil any more and needs to rebury itself? It has light sensitive eye spots and a brain to coordinate the incoming light stimulus and direct the muscles to rotate the abdomen and dig itself back underground.

A little critical thinking about these observations obliterates the myth. And that leads to greater understanding of one of the insect’s greatest feats - metamorphosis.

Histolysis

The part of the myth that is true is a lot of the larval body parts are broken down by enzymes in a process called histolysis to create a liquid-y reservoir of building blocks that will be used to recreate a new adult body. Let’s just consider the muscles. Some muscles from the larva get broken down for the rebuilding process, while other larval muscles persist and reorganize for new functionality in the pupa.

The new functions in the pupa include things like circulating hemolymph through the body and into newly developing appendages like legs and wings. And as time goes on, there’s less and less of the liquid and more of the newly forming adult body parts, like the muscles that are forming to prepare for adult functions like flight and walking. This means if you were to open up a pupa early on, there will be more fluid than if you open up a pupa near the time of its adult emergence; then there’s hardly any of the breakdown fluids left - they’ve been used up to make all of the adult tissues and organs.

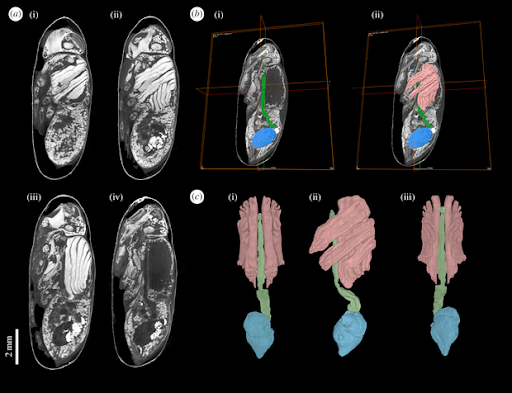

The process of adult formation within a pupa, which had long been hidden, is now viewable with new diagnostic capabilities. Below is an example from Martin-Vega, et al. (2017). It’s a time lapse of sorts that shows what goes on inside the pupa of a fly from inception to the 6th hour after pupal formation.

Even at the very beginning of pupal formation as shown in image (a), there’s still a lot of parts in there. None of these phases inside the pupa look like blowfly bisque to me.

And nearer to the time of emerging from the pupal stage as an adult, we can see from the next image that all of the adult anatomy is fully formed.

And if muscles are present and functioning in our soil-dwelling pupa from above, their movement is being coordinated by the still intact nervous system - a brain and neurons guiding and directing all of the muscular activity. This also includes light-sensitive eye precursors that can tell buried pupae if they’ve been unearthed and to start digging to get themselves back safely underground.

Awe Inspiring

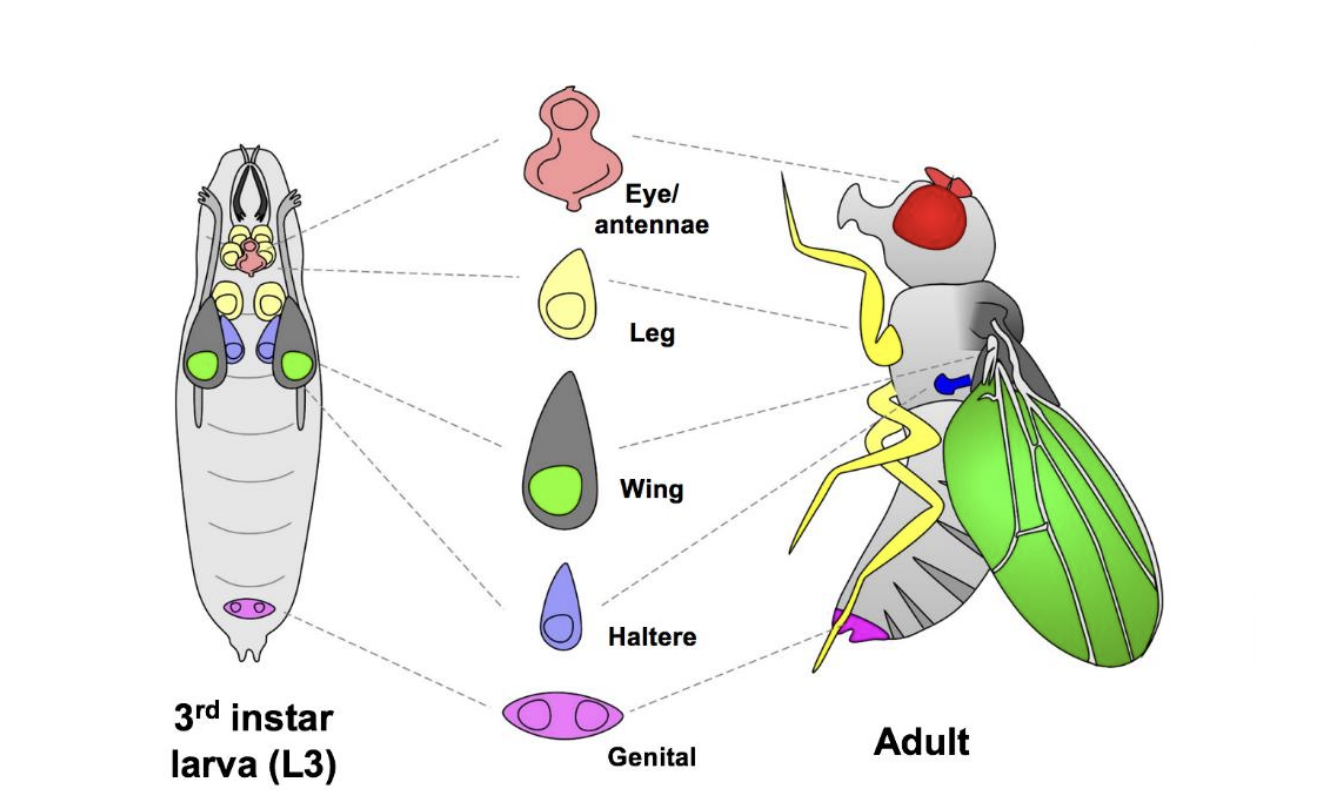

All of this pupal development is remarkable, but there is another element here that really inspires awe. They are called imaginal discs. No, they are not a figment of a hallucinatory entomologist’s imagination. The word imaginal stems from the Latin word imago meaning likeness or representation. In entomology, imago is the term to describe the final stage of an insect’s life cycle aka the adult. Imaginal disc, then, is the adjective form that is used to describe a grouping of cells - a blob of undifferentiated tissue - that live inside of an insect’s body from the time of it being an embryo until pupation. There are many kinds of imaginal discs in a larval body, all strategically positioned for their big moment. So, instead of forcing you to imagine what they look like, and thus avoiding that little irony, here are some imaginal disc images:

On the left is the late stage larva of a Drosophila fly inside of which lay of the various dormant imaginal discs of the soon to be adult body parts. The center column shows their shape and location in both the larva and adult and on the right what their fully formed shape and function is in the adult (From Kumar, S. R. 2020).

These discs of cells, little cyst-like bodies, are the foundational tissues for what will become adult body parts like legs, wings, mouthparts and genitalia.

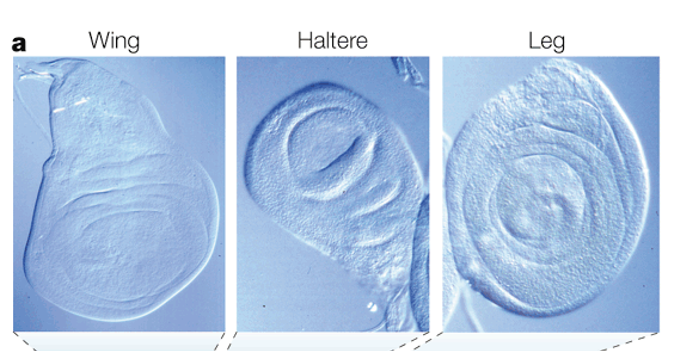

These images are micrographs of actual discs removed from a fly larva to show what a mass of undifferentiated cells looks like (image source unknown).

Think about it. A caterpillar has chewing mouthparts that mow through vegetation as it’s feeding and growing. But the adult moth or butterfly has a delicate, elegantly coiled tube for siphoning nectar from flowers.

Where the heck did the tube come from?? It was an imaginal disc of undifferentiated tissue lying dormant in the caterpillar head from the time it was still in the egg, up until pupation. During pupation the larva jettisoned the chewing mouthparts and cells of the imaginal disc were allowed to grow and develop into the siphoning tube, connecting to the muscles needed to help coil and uncoil it for reaching nectar sources in flowers.

What I find poetic about all of this is that everything an adult insect needs to be its best self has been inside of it from the beginning, it just needed the right conditions to grow and flourish. I think the same can be said for all of us too. Beautiful. Enjoy your holidays.

Sources

Shu, Runguo & Xiao, Yiqi & Zhang, Chaowei & Ying, Liu & Zhou, Hang & Li, Fei. (2024). Micro-CT data of complete metamorphosis process in Harmonia axyridis. Scientific Data. 11. 10.1038/s41597-024-03413-x.

L. H. Finlayson; Normal and Induced Degeneration of Abdominal Muscles during Metamorphosis in the Lepidoptera. J Cell Sci 1 June 1956; s3-97 (38): 215–233. doi: https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.s3-97.38.215

Dobi KC, Schulman VK, Baylies MK. Specification of the somatic musculature in Drosophila. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2015 Jul-Aug;4(4):357-75. doi: 10.1002/wdev.182. Epub 2015 Feb 27. PMID: 25728002; PMCID: PMC4456285.

Žnidaršič N, Mrak P, Tušek-Žnidarič M, Strus J (2012) Exoskeleton anchoring to tendon cells and muscles in molting isopod crustaceans. ZooKeys 176: 39-53. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.176.2445

Mary B. Rheuben; Degenerative Changes in the Muscle Fibers of Manduca Sexta During Metamorphosis. J Exp Biol 1 June 1992; 167 (1): 91–117. doi: https://doi-org.calpoly.idm.oclc.org/10.1242/jeb.167.1.91

Seth S. Blair, Chapter 130 - Imaginal Discs, Editor(s): Vincent H. Resh, Ring T. Cardé, Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition), Academic Press, 2009, Pages 489-492.

Ginés Morata, Peter Lawrence, An exciting period of Drosophila developmental biology: Of imaginal discs, clones, compartments, parasegments and homeotic genes, Developmental Biology, Volume 484, 2022, Pages 12-21.

Kumar, Sudiksha Rathan, "Investigating roles for RNA turnover processes in cell signaling through Drosophila melanogaster genetic mosaics" (2020). Honors Theses. 749. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/749.

Truman, James W. "The evolution of insect metamorphosis." Current Biology 29.23 (2019): R1252-R1268.

Martín-Vega D, Simonsen TJ, Hall MJR. Looking into the puparium: Micro-CT visualization of the internal morphological changes during metamorphosis of the blow fly, Calliphora vicina, with the first quantitative analysis of organ development in cyclorrhaphous dipterans. Journal of Morphology. 2017; 278: 629–651. https://doi-org.calpoly.idm.oclc.org/10.1002/jmor.20660

Hall, Martin JR, and Daniel Martín-Vega. "Visualization of insect metamorphosis." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374.1783 (2019): 20190071.

Snodgrass, Robert Evans. "Insect metamorphosis." (1954).